BANNED By Simon Ruston & Chris Johnson

BANNED

By Simon Ruston and Chris Johnson

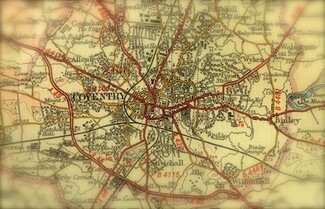

There has recently been publicity concerning the intention of Coventry City Council to seek an injunction against Travellers covering 100 pieces of land: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-coventry-warwickshire-29175493 An injunction is a court order which requires the persons named to not do something, in this case pull their caravans onto land. If they do so they risk fines or imprisonment. In the case in Coventry, the injunction would effectively ban the Travellers from all council owned land.

What is the legal position with regard to such injunctions?

In Meier & ors v Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (SSEFRA) [2009] UKSC 11, the SSEFRA, which is responsible for the Forestry Commission, sought possession against a group of Travellers on an unauthorised encampment on land at Hethfelton Woods in Dorset. A possession order is a court order requiring a person or persons to leave a property or land. If you do not comply with a possession order you can be evicted from the property or land in question. At the same time, the SSEFRA sought a wider possession order covering a large number of other woods in that part of Dorset to which it was suggested the Travellers might move to and an injunction covering all those pieces of woodland.

In the county court the judge, Recorder Norman granted the possession order in respect of Hethfelton Woods but refused to grant the wider order or the injunction. The SSEFRA appealed and the Court of Appeal (CA) granted both the wider possession order and the injunction. Two of the Travellers, Ms Horie and Ms Rand, appealed to the House of Lords (which, by the time the judgment was handed down, had transformed into the Supreme Court).

The Supreme Court concluded that the Civil Procedure Rules which, amongst other things, set out the rules on the use of possession orders do not permit the grant of a wider possession order and overturned the CA’s judgment on that point. The simple point was that a landowner could not obtain a possession order in respect of land in circumstances where that landowner already enjoyed uninterrupted possession of it. Lord Rodger stated (at para 9):

[T]he Forestry Commission were at all relevant times in undisturbed possession of the parcels of land... That being so, an action for the recovery of possession of those parcels of land is quite inappropriate.

This is is obviously very useful in confirming that possession orders cannot be granted on land where no one has pulled on. However, the Supreme Court expressed the view that the remedy of an injunction could be sought in circumstances where there was a risk that a Gypsy or Traveller would move from one unauthorised encampment on land owned by a public body to another parcel of land also in that public body’s ownership. The Supreme Court, therefore, upheld the CA’s grant of the injunction.

Lord Neuberger went further and indicated that, in his view, the failure by the Forestry Commission to follow government guidance on unauthorised encampments with regard to the other parcels of land, should not preclude the injunction being granted. He stated (at para 87):

I do not see how [reference to the guidance] could have justified an attack on the lawfulness of the Secretary of State seeking an injunction to restrain the defendants from setting up such unauthorised camps...I incline to the view that the existence and provisions of the 2004 Guidance could be taken into account by the Court when considering whether to grant an injunction and when fashioning the terms of any injunction.

Lord Neuberger was referring to the Guidance on Managing Unauthorised Camping (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister) which, amongst other things, advises that local and other public authorities should take account of welfare enquiries before deciding whether to evict an encampment.

The Supreme Court’s decision does not explain what considerations would arise for determination if such an application for an injunction is made. No doubt defendants will argue:

a) that the test for granting a quia timet injunction (an injunction to prevent a possible future occurrence) has not been met;

b) that the principles laid down by the House of Lords in South Buckinghamshire DC v Porter [2003] 2 AC 558 (a planning injunction case) should be applied, i.e. that a judge should not grant an injunction unless s/he is sure that prison would be contemplated and that, in order to come to such a conclusion, s/he would need to have regard to all the circumstances, including the personal circumstances of the individuals concerned;

c) that, notwithstanding Lord Neuberger’s comments regarding the government guidance, a failure to have regard to it and to follow it (unless there are good reasons for not doing so) would render a decision to seek an injunction unlawful;

d) that the grant of an injunction, and particularly a wide ranging injunction, would have a disproportionate impact on the ability of the defendants to live their way of life and would breach their rights under Article 8 of the European Convention (the right to respect for private and family life and home).

Chris Johnson (chrisjohnson@communitylawpartnership.co.uk)

Travellers Advice Team (TAT) at Community Law Partnership (CLP)

TAT operates a national Helpline for Travellers on 0121 685 8677, Monday to Friday 9.00 am to 5.00 pm

Simon Ruston, Ruston Planning Limited, Independent Planning Consultant specialising in Gypsy and Traveller work

Simon can be contacted at simon@rustonplanning.co.uk or on 07967 308752/0117 325 0350

8 October 2014